Tales From the Wild Side

Fall 2021

Board of Directors

President Ilka Milne

Vice-President Mike Hammond

Secretary Gaby Emond

Treasurer Henry Van Ael

Committees

Newsletter Ilka Milne & Bob Saunders

Website Ilka Milne & Bob Saunders

Events Ilka Milne & Bob Saunders

Boardwalk Ahlan Johanson & Mike Hammond

Publicity Henry Miller & Ilka Milne

Stewardship Liaison Gaby Emond

Presidents Message

Now almost two years since our club revival plans were interrupted by the pandemic, we’re once again working on re-booting our group activities. On a recent zoom meeting (who had even heard of such a thing two years ago!), with the other Northern Ontario club leadership I learned that most of them experienced a growth in membership, as people reached out to join online meetings and activities. For some new members it was a chance to check in with others in their community, while other new members joined to virtually visit their vacation land.

Our experience has been different so far, as we struggle more than other clubs with inconsistent internet access and because we were cut off from the large proportion of our members who are seasonal residents or American. No one executive member had the internet to support an online meeting and we couldn’t access a public space to work from.

But, with the recent re-opening of public spaces in Ontario we now have an opportunity to connect again. Although we are restricted to how many people can gather in one room, and in most public venues we require everyone present to be double-vaccinated, we hope to create a hybrid meeting/public event where we gather the locals together in a space with good internet, and connect with our remote friends online. Throughout the fall and winter of 2021 we will start up this model and we hope to see you there!

Summer 2021 was the first of the five year current Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas project, locally coordinated by Bob Saunders. A small contingent of volunteers has already made a great headway in covering local priority squares. Recently a work party made some repairs at the Cranberry Peatland Interpretive Trail and thanks again to Ahlan Johansen and Mike Hammond for getting the trail ready for winter. A recent field trip to the Oak Grove has resulted in well flagged trails as well as both a hard copy and online trail map.

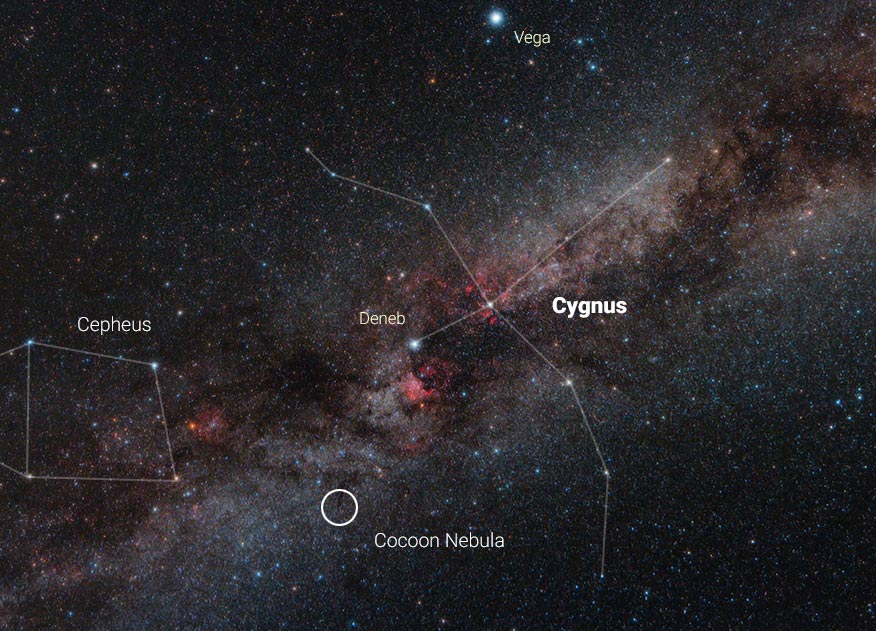

IC 5146 THE COCOON NEBULA

Article by Fred Pugh

The Cocoon Nebula or IC 5146 (Index Catalogue) is an emission, reflection and absorption or dark nebula found in the constellation Cygnus near the border of constellation Cepheus (figure 1) and was discovered in 1899 by Thomas Espin. The summer and fall are the best times for viewing when Cygnus is high in the sky. At magnitude 7.2, it is hard to see without a telescope or a camera but in a very dark sky some can see it with binoculars. The angular size of the bright nebula is a small 12 arc minutes but the dark absorption lane runs for 1.7 degrees or about 3 full moon widths. There is also a bright open star cluster composed of young hot stars that is associated with the nebula.

The Cocoon Nebula is almost 4000 light years away and the bright part of the nebula is about 15 light years wide. There is a giant molecular cloud composed mostly of hydrogen and dust which gives it the distinctive red – pinkish color. This molecular cloud is a stellar nursery where many new stars are being born. The bright star at the centre of the nebula was formed only about 100,000 years ago and is responsible for ionizing the brightly glowing nebula and is carving out a cavity in the centre of the cloud. The dark cloud and lane that trails off from the brightly colored nebula actually has its own designation which is Barnard 168. This cloud of dust is so thick that it hides the stars behind it. The photo below (figure 2) was taken with a Canon DSLR and a 200 mm lens mounted on a tracking mount. Both the Cocoon Nebula and Barnard 168 are clearly visible.

I took this photo of IC 5146 the Cocoon nebula on August 8, 2018 (figures 3, 4). It was a warm, calm night near the new moon and the sky was beautiful. Since it was just over 6 weeks past the summer solstice, the night was not as long as I would have liked but everything went well and I managed to get 18 good light frames to stack. I was very pleased with the way the data looked and recently went back to re-processed this data with some of my newly learned skills and am much happier with the result. The Cocoon Nebula like the Veil Nebula lies in the heart of the Milky Way so the view is loaded with stars. During processing I toned down the brightness of the stars just a bit to make the nebula pop a little more.

My work flow for creating this photo is as follows:

Telescope – Stellarvue SVA130T 5.1” Apochromatic Refractor

Focal length – 650mm

Focal ratio – f5

Camera – SBIG STF 8300C

Camera Temperature – set to -20C

Mount – Celestron CGEM DX

Light Frames – 18 at 5 minutes each

Dark Frames – 9 at 5 minutes each

Flat Frames – 10 at .01 second each

Dark Flat Frames – 10 at .01 second each

Inspected all frames for tracking errors and other problems, all were kept

Converted all frames from RAW to FITS files

Stacked in deepskystacker to reduce noise and enhance signal

Imported into Photoshop to stretch data, smooth remaining noise, enhance color and sharpen

Winter Finch Forecast 2021-2022

The winter finch forecast is created by Tyler Hoar and is based upon numerous observations by individuals from across norther Canada and the US. For his complete forecast visit the Finch Research Network

The year’s flight should not be an irruption year, but some southward movement should be into their normal southern wintering areas in Southeastern Canada and Northeastern United States. However, there will be movement of most finches varying by species and location in the boreal forest.

Northwestern Ontario was significantly impacted during the summer by drought, high temperatures, and forest fires resulting in poor berry and cone crops. In our region (NW Ontario) expect most finches (Pine Siskins, Red and White-winged Crossbills, Evening Grosbeaks, Pine Grosbeaks, and Common and Hoary Redpolls) and irruptive passerines (Blue Jays, Red-breasted Nuthatches, and Bohemian Waxwings) to move out of the boreal forest looking for feeders in towns or suitable food sources further south.

Oak Grove Trip- Oct 2021

On Sunday October 24 we took an exploratory trip out to the Oak Grove to lay down some tracks on the existing trails, record trail conditions and sites of interest for future club field trips. We flagged the trails for future reference and created both an interactive google map which can be followed in real time on your phone, and a google earth map for printing. The eastern boundary is difficult to find north of the Outcrop Trail, but we used some key waypoints and google earth’s pro version to map its location so we can follow this to flag it in the future. All the other trails are possible to find ‘with your feet’. These trails are well travelled by wildlife such that a rut has worn in the earth. Even when you can’t see the opening in the trees you can feel the depression beneath your feet. The problem on previous visits has been that concentrating on your feet leaves you oblivious to all the birds and butterflies flitting about you!

In spite of the main goal being trail finding, we did notice many interesting fungi. Of course, at this time of year most of the fleshy mushrooms have vanished, but the heavy oak leaf litter did protect some gems. One of these was the Craterellus fallax (or cornucopioides (both black chanterelles, but one has a more easterly range and one more westerly) found at the margin of the rock outcrop. Regardless of its precise species, this is a choice edible. Dried and powered it is vaguely cheesy and contributes to soups, souffles, sauces and scrambled eggs. It is apparently known as the poor man’s truffle.

There were many other interesting finds, but most of them will need some work and spore prints to identify. The Birch Polypore (Fomitopsis betulina), however, is quite common on the site and is worth a few words. This fungus is the one which was discovered in the possession of the 5300 year old man found in the ice in 1991 in the Alps. As this has medicinal properties associated with it and has been used that way for thousands of years, the assumption was that the ice man would have been carrying it as a medicine in his first aid kit. It is also known as the ‘Razor Strop’ as it has been used as a surface for finishing the edges of razors, and apparently has been useful as a tinder and as a mounting material for insect collections.

The Tinder Polypore Fomes fomentarius, also known as amadou, was also in abunance. This has been used since ancient times to help start fires and can be processed to create fibers for making clothing. Many of the mature Trembling Aspen are infected with Aspen Bracket Phellinus tremulae.

We are sure to plan a trip in spring, when bloodroot and orchids are in bloom and the area’s warblers are back for the summer. But with the many mushrooms which can be found associated with oak trees, this is also likely to be an interesting place to visit earlier in the fall.

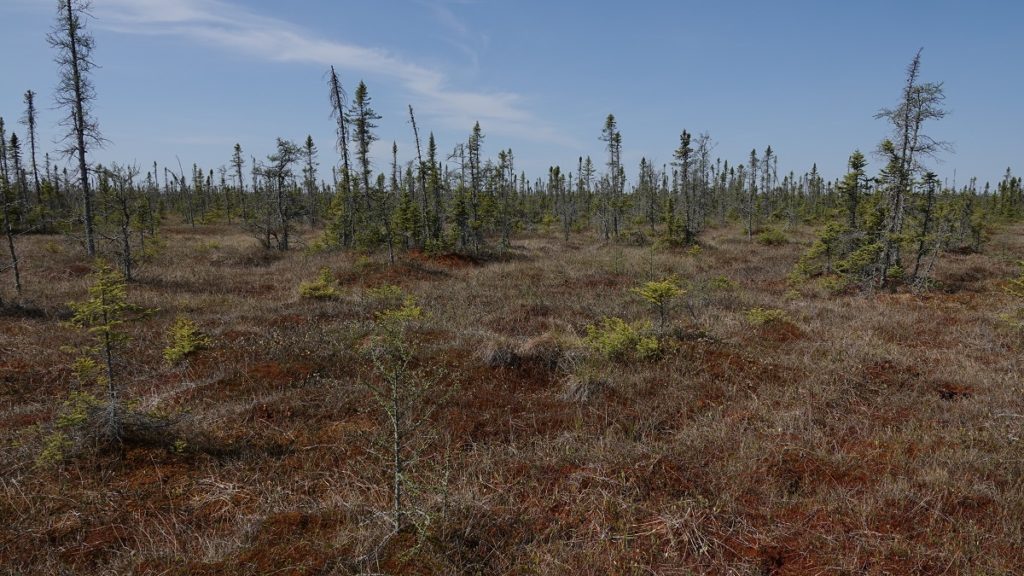

Boardwalk Maintenance Work Party

On Saturday October 2 a party of volunteers gathered to make some repairs and board replacements at the Cranberry Peatland Interpretive Trail. Annual repairs are working out to about a dozen boards, and we noted that one section will have to be jacked up and then shimmed with something in the spring. There is a wood duck nest bundle that needs replacing, and we’re thinking of putting it out of reach of walkers on the other side of the waterway this winter so that ducks won’t be disturbed if they take up residence.

It was a mild and overcast day. While the bog produced a moderate crop of small cranberry this year, mushroom growth has been profuse.

Poetry Corner

Autumn

by Adelaide Crapsey (1878-1914)

Fugitive, wistful,

Pausing at the edge of her going,

Autumn the maiden turns,

Leans to the earth with ineffable

Gesture. Ah, more than

Spring’s skies her skies shine

Tender, and frailer

Bloom than plum-bloom or almond

Lies on her hillsides, her fields

Misted, faint-flushing. Ah, lovelier

is her refusal than

Yielding, who pauses with grave

Backward smiling, with light

Unforgettable touch of

Fingers withdrawn…Pauses, lo

Vanishes…fugitive, wistful…

November Night

by Adelaide Crapsey

Listen.

With faint dry sound,

Like steps of passing ghosts,

The leaves, frost-crisp’d, break from trees

And fall

.

First Snow, November: A Photo Essay

The first snow of November hit the Rainy River District hard. The storm began as light rain on Wednesday November 11, becoming heavier as the day progressed. The rain continued through the night, By morning there was about a cm of snow on the ground. A mix of rain and snow continued all Thursday, changing to snow in the evening. By Friday morning heavy wet snow 20 – 25 cm deep had covered the ground, bending and breaking trees and shrubs. Warmth seeping up from the ground left the bottom quarter of the snow sloppy and wet. The storm eased off during the afternoon, by then of the major roads in the region had been closed. Considerable more snow would have accumulated had not much of the precipitation occur as rainfall.

Mosses, Bogs and the Carbon Conundrum

Article by Ilka Milne (reprinted from the Fort Frances Times November 17, 2021)

Mosses are primitive plants that, while small and easily overlooked, control water in many of our district’s ecosystems and are vital in keeping atmospheric carbon in balance. They are unlike trees, shrubs, herbs and ferns in having no specialized transport tissue (plu mbing for moving waterfrom roots to leaves). Their leaves are just one cell thick. They have no flowers or seeds. Instead they reproduce by spores, but also by cloning themselves from fragments. In spite of their association with damp locations, mosses are remarkably capable of surviving drought. They can reabsorb water as soon as it is available, have incredible powers of cellular repair and can start to photosynthesize once re-hydrated even after being stored inside in a collection envelope for months.

Their big impact on the environment is partly due to their small size. Being low to the ground and without transport tissues they have large specialized leaf cells in direct contact with their environment. This means they are capable of rapid water absorption and thus absorb extreme rainfall events. Their ability to clone themselves from fragments means they can rapidly colonize almost anywhere and both create and stabilize soils. They can gain scarce nutrients from poor soils and even bare surfaces because they are very good at cation exchange. They dump positively charged hydrogen ions into the environment to bump loose and trade for a positively charged nutrient ion. They are much more effective than many other plants at this trick, which in some situations allows them to take over, by increasing the acidity so much that other plants can no longer access nutrients. This, and their ability to create and tolerate waterlogged conditions is how a peat bog is built.

Last week the World Wildlife Fund released a map of Canada’s peatland carbon stores, created by fascinating research out of McMaster University’s Remote Sensing Lab. It shows dense carbon stocks in a huge swath of Northwestern Ontario and northern Manitoba, as well as significant deposits around Lake Winnipeg. Of interest locally is that the machine learning algorithm they used to create this map picked up one of our bogs, the Agassiz Peatlands Provincial Park near Gameland, as one of the denser deposits. https://wwf.ca/carbonmap/

Soils store much more carbon than plants, and among soils peatlands are the richest in carbon. Peatlands get their name from partially decomposed plant matter which we call ‘peat’, much of it mosses such as sphagnum moss. Peat can accumulate to great depths when mosses grow over themselves over the centuries but don’t fully decompose in the cold, acidic and waterlogged environments where they thrive. The WWF map background estimates that in northern Canada, one square metre of peatland contains about five times as much carbon as the same area of Amazon rainforest. While the carbon stored in typical tropical or boreal forest soil is between 100 to 500 years old, boreal peatland carbon can be up to 10,000 years old. This means that although our bogs are carbon sinks, it is important to recognize them as old sinks more likely to leak their vast carbon stores than to be of help in drawing down carbon dioxide if we’re not careful with them.

Bogs do not grow quickly, and the carbon in them represents carbon locked in over a long period of time. In Alberton Township the Rainy River Valley Field Naturalists established an interpretive boardwalk trail in a bog which was mined for moss during the second world war. (For further information about the Cranberry Peatland Interpretative Trail click here). While walking the trail you will feel as though you are surrounded by a soft cushion of deep sphagnum, but if you explore the area on google maps you’ll notice that although it was last mined more than 50 years ago, you can easily see traces of the harvest. As Canada is home to one quarter of the world’s remaining peatland carbon stores, disturbance for development, drainage, thawing and increased decomposition of our peatlands is likely to put us on the wrong side of the carbon balance sheet.